4 hours ago

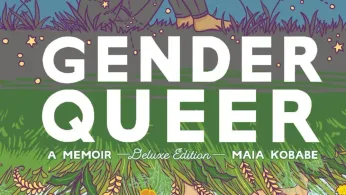

"Gender Queer," America’s Most Banned Book, Receives Deluxe Edition Release

READ TIME: 3 MIN.

"Gender Queer: A Memoir", written and illustrated by Maia Kobabe, has become one of the most talked-about—and most frequently challenged—books in the United States. First published in 2019, the memoir chronicles Kobabe’s personal journey of self-discovery, exploring themes of gender identity, sexuality, and the challenges of existing outside the gender binary. Now, the graphic memoir is receiving a deluxe hardcover edition, released by Oni Press and distributed by Simon & Schuster, offering readers new exclusive content and a renewed spotlight on its cultural significance .

The deluxe edition of "Gender Queer" features a brand-new cover, exclusive artwork and sketches from Kobabe, a foreword by ND Stevenson (the creator of "She-Ra and the Princesses of Power" and writer of "Lumberjanes"), and an afterword by Kobabe. This edition is designed not only to celebrate the book’s literary and cultural impact but also to provide additional context and insight into Kobabe’s creative process and the memoir’s message .

The memoir itself has been praised for its honest, accessible exploration of nonbinary and asexual identities, making it a valuable resource for those questioning their own identities or seeking understanding as allies. Reviewers have lauded its “cathartic” storytelling and its utility as both a personal narrative and a broader guide to gender identity issues .

Since its initial publication, "Gender Queer" has garnered critical acclaim, including a 2020 Alex Award from the American Library Association and recognition as a Stonewall Honor Book . However, the memoir’s candid depiction of gender, sexuality, and certain sexual experiences has also made it a frequent target in the United States’ escalating wave of book challenges and bans.

The American Library Association has ranked "Gender Queer" as the most challenged book in the nation for three consecutive years (2021–2023), with objections often citing the presence of sexually explicit illustrations . The increase in attempted bans coincides with a broader movement in U.S. politics to remove LGBTQ+ content from school and public libraries, with "Gender Queer" often at the center of these debates .

In fact, "Gender Queer" has been recognized by the Guinness World Records for being the “most banned book of the year,” underlining its place in the ongoing struggle over freedom of expression and LGBTQ+ visibility .

Originally conceived as a way for Kobabe to explain eir identity to family, "Gender Queer" has since become an important touchstone for many readers navigating their own experiences with gender and sexuality . The memoir traces Kobabe’s journey from childhood through adulthood, covering formative moments such as coming out, first relationships, and the complexities of being nonbinary and asexual .

Reviewers and LGBTQ+ advocates have highlighted the book’s significance for queer youth and their families, not only for its representation but also for its educational value. As noted by Booklist, “"Gender Queer" exists so a new generation can see the words and experiences to help them feel whole and seen” .

The memoir has also played a role in increasing awareness and empathy around nonbinary and asexual identities, areas often underrepresented in mainstream media. School Library Journal called "Gender Queer" “a great resource for those who identify as nonbinary or asexual as well as for those who know someone who identifies that way and wish to better understand” .

The release of the deluxe edition comes at a time of heightened scrutiny for LGBTQ+ books and authors, with state legislatures, school boards, and advocacy groups debating who gets to decide what stories are available on library shelves . For many LGBTQ+ advocates, the continued popularity and rerelease of "Gender Queer" serve as both a rebuke to censorship and a celebration of queer narratives.

The deluxe edition, with its additional content and enhanced presentation, is positioned not only as a collector’s item but also as a renewed statement of the importance of free expression and diverse storytelling. For Kobabe and many readers, this edition represents resilience in the face of suppression and the enduring power of queer voices in literature .

As debates over book bans and LGBTQ+ representation continue in the United States, the story of "Gender Queer" highlights the intersections of art, identity, and civil rights. The memoir’s journey—from a self-published zine to a widely recognized, frequently banned, and now deluxe-edition bestseller—mirrors broader cultural conversations about who gets to tell their stories, and who gets to access them .

For readers, librarians, and advocates, the deluxe edition of "Gender Queer" stands as a testament to the importance of inclusive literature and the need to defend the rights of all people to see their lives reflected in books. As the conversation around censorship and representation continues, the legacy of "Gender Queer"—and its new deluxe edition—remains a powerful reminder of literature’s role in fostering empathy, understanding, and community .