Mar 13

Actor Sean Leviashvili Finds Authenticity in SpeakEasy's 'Cost of Living'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 8 MIN.

SpeakEasy Stage Company brings Martyna Majok's Pulitzer Prize-winning play "Cost of Living" to Boston in a production directed by Alex Lonati. Set against a backdrop of economic inequality, the play is an exploration of how hearts and bodies alike can face challenges that erase what once was – or open up to new potential.

The story spotlights two relationships. Eddie (Lewis D. Wheeler) and Ani (Stephanie Gould) are a longtime couple whose bond collapsed not long before a life-altering accident left Ani paralyzed. Now the former life partners struggle to salvage what's left and, possibly, build a new future.

Meanwhile, John (Sean Leviashvili), a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton and the son of a wealthy family, sets about hiring a home health aide. John has cerebral palsy, a neuromotor condition that, in his case, is debilitating. He needs assistance with personal grooming such as shaving, bathing, and getting dressed. John hires Jess (Gina Fonseca), a first-generation immigrant whose smarts and drive got her an Ivy League education of her own, but whose prospects are much more limited. Both are hard-headed and a touch abrasive, but as they warm up to each other new possibilities seem about to unfold.

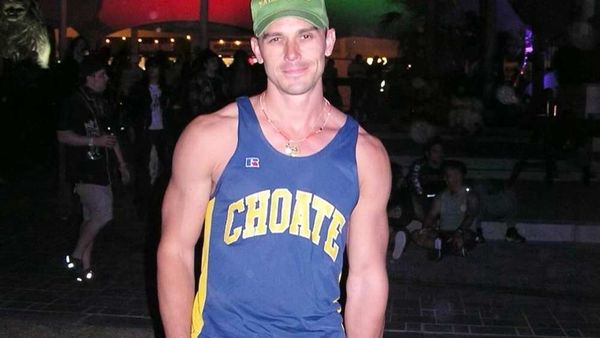

EDGE chatted with Leviashvili about the role of John. A queer actor with cerebral palsy, Leviashvili is a graduate of Northeastern whose career has taken him to NYC and LA, seen him write, direct, produce, and star in the short film "Limp," and work on the production of shows as varied as "My Crazy Sex," "Smile," "White Water Summer," and "Below Deck Adventure."

Sean shared his insights about what the play has to say about class, disability, love, life, and the costs those things entail.

Source: Nile Scott Studios

EDGE: Tell me about your character, John.

Sean Leviashvili: I believe John has the biggest story arc in this play, and that's why I'm really excited and honored to play him. The first scene [he's in] is the first day of the rest of his life: He's getting to pick his aide, who's going to help him be the best version of himself in this brand-new chapter at Princeton as a Ph.D. student. He picks this girl who's kind of edgy.

The second scene that he's in, in a weird way, it's his coming out. He's getting the chance to explain how his body works to someone new. Explaining his body is his way of revealing who he is. Then the shower scene, that is his chance to test drive skills he has never been able to before – and by that, I mean the flirting.

EDGE: Speaking of the showering scene, the stage directions are for you to be nude on stage. Was that uncomfortable for you?

Sean Leviashvil: There is a small edit there, where I'm going to be in a sheer covering over my private parts – but I still am going to have to be mostly nude. I'm learning to get comfortable with it. We have a partial shower that's constructed so that I'm not going to be fully exposed. You know, my family's coming to this and, um, they haven't seen this since, you know, I was two years old. I'd like to keep it that way for now.

[Laughter]

But more than the partial nudity, we've worked with an occupational therapist to learn what is the right step-by-step routine to properly shower someone like John. We are working to make this scene be authentic and comfortable for everyone involved. Luckily, I have this this amazing scene partner, Gina Fonseca. She has been wonderfully patient and incredibly attentive.

EDGE: I think there's a comment of some sort in the play's implicit comparison of being disabled from birth versus becoming disabled later in life, and people discovering love versus trying to reclaim it.

Sean Leviashvili: I think so, too. You know, it's funny when people explore or try and understand disability, it takes on so many different forms. There are disabilities you can't see, there's disabilities you can't understand. There are some that are more pronounced. There are some that are more nuanced. I think that this play explores that quite eloquently.

I think it's very interesting to look at what John is striving for – the same things all of us are: To succeed, to find love, to explore yourself. He's very inexperienced. One thing I like to point to in the script is [how] he tells jokes a grandfather might make, which shows that he doesn't quite know how to talk to people his own age and just chill.

EDGE: That's so relevant to growing up queer, too.

Sean Leviashvili: Yes, I completely agree with that. I have been able to relate to John through the lens of disability, and also through the lens of my sexuality as a gay man. I didn't kiss anyone 'til I was 19, and [it wasn't until] a few years later I started dating. I had no clue what I was doing, and I had no reference, either. You don't have people saying, "Oh, I want you to meet this person," or, "Try this, try that." You're just hearing it through the grapevine: "This is the bar you should go to," or, "This is an app you should try." Maybe you'll meet a lunatic, or maybe you'll meet someone – it's 50/50 when you knock on those doors.

EDGE: That's kind of the plot of your film, "Limp."

Sean Leviashvili: "Limp" was basically a true story. I went on a date with a guy, and we had the nicest date I'd had in a long time. Towards the end of the night he said, "Oh, is your leg okay?" And I said, "Yeah, I just hurt myself at the gym earlier this week." The bigger lie is that I said I went to a gym.

[Laughter]

Sean Leviashvili: I decided to say this because I didn't want his opinion on my disability to change the time we had that night. And then, day by day, the communication sort of fizzled, and I always wondered, what happened? Years later we reconnected, and I asked, "What happened that night? Because I thought we had a really great time." And he goes, "You know, we did have a great time – and I knew you were lying." He said, "I don't hold that against you. I had just broken up with someone who lied a lot." It just didn't land right with him at the time, and he would have much more appreciated me be honest.

So now I'm at a point where, at least on Hinge and Tinder – I don't go on Grindr, because it's just, whatever – but I do disclose now, just to put that out there before meeting people.

Source: Nile Scott Studios

EDGE: There's all kinds of debate around who gets cast into what kind of role. How would you welcome it if they didn't think about things like disability when casting?

Sean Leviashvili: My hope is that casting can expand and embrace people with disabilities for roles that don't spell it out, because in my life that's reflective. I've been a best friend, I've been a brother, I've been a colleague, a coworker. I would love to see people with disabilities be considered for [roles] where the disability is not the only storyline.

EDGE: How about the other way around? Like if they made "My Left Foot" today, should somebody other than Daniel Day-Lewis play the main role?

Sean Leviashvili: I think when it's a specific person, maybe you want to find the actor that can best reflect who that person is. Here's my example: Freddie Mercury. He's a queer icon, [but] I think the person that would get that role would be the person that best reflects Freddie [regardless of whether or not he is queer].

But I think for something like "Love, Victor," which is about queer kids, we can make a better effort to try and find queer actors, because it's not only about the reflection of the character, [it's about] the content. These queer actors may be able to weigh in on the storylines in a more compelling way. If it's a role that is about a demographic, I think it would be great to make a concerted effort to find people that reflect that experience, versus reflecting the character.

For [a role] like John, who has cerebral palsy, I do think it's important to cast someone that has a disability. And Martyna [Majok], the playwright, spelled that out in the script: She literally says, "Please cast people with disabilities for the roles of Ani and John." I absolutely love and appreciate that.

"Cost of Living" runs through March 30 at the Stanford Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts. For tickets and more information, follow this link.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.